A Long Approach to the Eiger North Face by Yuki Fujita

/

Around the late 1950s, mountain climbing became a popular recreational activity in Japan. Consequently, the number of climbing accidents increased and the news media began reporting these accidents. I remembered being amazed by the news photos of stranded rock climbers on huge, sheer cliffs. I had a curiosity for how the climbers got there, and that curiosity led me to mountain climbing later. I cannot remember when I started climbing, but it was in the early 1960s, during my high school days.

Around the 1960s leading Japanese climbers started appearing in the Alps, and subsequently, news of those ascending those hard classic routes often made headlines and appeared in popular mountaineering magazines. After learning about the three great north faces in the Alps; Matterhorn, Eiger, and Grandes Jorasses, I began dreaming of climbing the Matterhorn north face because of its iconic beauty. The other two were not in my mind since those were more difficult. However, as my climbing techniques advanced, my goal had changed to the Eiger.

Solo aid climbing under the roof 200ft above ground. Note: Heavy mountain boots.

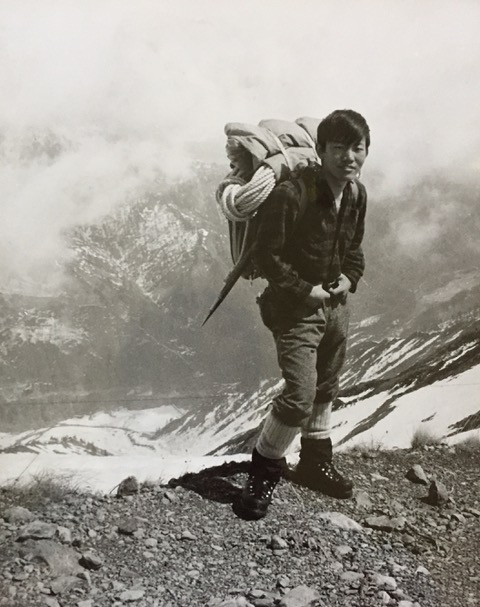

Descending on the ridge from Mt Shirouma (~10,000ft) after 2 bivouacs.

Winter technical climbing, experimenting With crampons on the rock.

After graduating from high school in Japan, I was invited to come to America by my mother’s friend, Millie McCoy, in southern New Hampshire. During the first two years at the McCoy’s, I attended a junior college. However, I could not go climbing since that was an unorthodox activity in my American mother’s mind. But because of my strong desire to climb, she somehow ran across the Appalachian Mountain Club (AMC) and suggested that I join them.

Unfortunately, the AMC during the late 1960s had many rigid rules and procedures for climbing activities which made it unappealing for me. Consequently, I left after one season. About the same time, I started a four-year college at Lowell Technological Institute. Initially, I was excited about finding an Alpine Club on campus, however, the name “alpine” was misleading as the main activities were hiking and snowshoeing. Obviously I was disappointed. Fortunately the president of the club suggested that I teach the group how to rock climb. So I immediately organized a technical climbing group, which led to funding from the Student Council for the purchase of climbing ropes and other climbing gear.

While at Lowell, we spent many weekends in the White Mountains for rock and ice climbing. However, as newcomers, they were not equipped nor ready for alpine climbing. For my own training, I often soloed up easy mixed routes (no name routes) in Huntington Ravine and Franconia Notch, and sometimes slept on snow covered ledges without sleeping bags. Of course I couldn’t sleep well on those nights, but I dreamed of the Eiger.

After climbing no name routes on the Pinnacle.

After graduating from Lowell, I went to graduate school in southeastern Idaho close to the Rocky Mountain Range. Luckily before the start of school, I met a British mountaineering instructor, Bill March. He formerly taught at Glenmore Lodge, i.e., National Outdoor Training Centre in Scotland. That year he came to Idaho State University (ISU) to teach a Mountaineering Safety course as part of the outdoor education curriculum for the School of Education. Although I was in the School of Engineering, I signed up for his course. Surprisingly he asked me to be his student assistant. There were several experienced rock climbers among the students, but he selected me based on my safe climbing and mountaineering experiences.

The mountaineering skills I had learned were primarily from Japanese mountaineering textbooks so I was afraid something might have been missed. He taught us systematically covering all aspects of mountaineering safety, and even gave us a written examination at the end of each semester. By the end of the course, I realized that there were no missing subjects in my self-training. The course required us to attend weekend outdoor climbing events. By observing Bill, I learned a lot of the efficiencies of climbing, which were very important for long alpine routes particularly for higher altitudes such as the Alps. Also, I enjoyed listening to his Alps stories; I knew they would be useful in the future.

Goofing off during the lunch break at Bill March’s climbing seminar. See a 7Up can on my tool, and wind-pants down to my ankles, and no rope.

Placing an ice screw. Note: Needed both hands. Hammered in a few inches, then twisting with ice tool.

Besides the curriculum I climbed with Bill on numerous occasions. During the spring semester break, we tried to scale the Nose on El Capitan. On the first day we aided up to the Sickle Ledge. But that night we got soaked by freezing rain, and had to struggle with the possibility of hypothermia. The next morning, we safely rappelled 550 feet down to the ground. We learned the hard way that nobody should attempt to climb the Nose in March, except Bill March.

After ISU I got an engineering job in Idaho Falls where the Grand Teton was only 3 hours away. However, I didn’t summit the Grand Teton until recently. During my grad school year, I married a woman who was unsympathetic to climbing. As a result, climbing became a low-key activity for almost 20 years, and then the marriage eventually broke up. Sadly, I watched my climbing gear become antiquated, and my climbing clothes go out of fashion. Also, I lost my appetite for alpine climbing after moving back to New England’s rounded hills. Worse, my climbing partners during my college years were nowhere to be found. The dream of the Eiger turned into a small hope, and it had to wait until my daughter grew up.

When my daughter became of high school age, I gained some free time for rock climbing. Initially I started going to Crow Hill alone for bouldering but, sooner or later other climbers invited me to hop onto their top-ropes. In a short time, Crow Hill became my routine place to go, twice a week after work and every weekend. Eventually I became acquainted with the AMC Boston Mountaineering Committee members such as Eric Engberg, Judy Bayliss, and David Oka. For winter, I gained a few occasions to swing my ancient ice axes in a vintage nylon outfit. When my daughter went to college, I began to think of the Eiger more seriously since I was already in my forties. With gaining more free time and climbing partners, I began to update the climbing gear and outfit. Initially hesitant because of the bad memory of the old AMC, I finally accepted David Oka’s persistent invitation and presented myself to the Harvard cabin for the AMC ice program, thank you, David!

As the first step toward the Eiger, I went to the Alps for the first time in my life and traveled straight to Kleine Scheidegg to see the Eiger Nordwand i.e., the Eiger North Face. My eyes followed the Heckmair’s 1938 route: the First Pillar, Ice Fields, the Traverse of the Gods, and then to the White Spider. Then, I took the train to Jungfraujoch for climbing Jungfrau. After Jungfrau, I traveled to Chamonix for alpine climbing. For acquiring a climbing partner, I camped at the Argentière campground where many British climbers were staying. My idea was correct and I found a British climber, Paul Cleary, who was also looking for a partner.

Paul and I hit it off surprisingly well and we ended up climbing together for over 20 years in the Alps. We climbed numerous very hard (TD and ED) routes. The Eiger Nordwand was also one of his dream climbs. In the mid 1990s, we climbed Mittellegi Ridge of the Eiger as a reconnaissance and then descended on the West Flank. The view of the north face from the West Flank was very impressive by its enormous size, twice as tall as El Capitain. We camped in Grindelwald for two weeks, and waited for an opportunity to climb the Nordwand. However, every day was too wet. Disappointed, we would have to come back another time.

We didn’t try the Eiger Nordwand until many years later since we were preoccupied by other routes in the Alps. At the age of 61, we successfully climbed the north face of Grandes Jorasses via Walker Spur. Then because of my age, I quickly turned my concentration back to the Eiger.

One of the most dangerous aspects of the Eiger Nordwand is rock fall. For most of the falling rocks, you won’t hear its sound until it hits near you or it hits you. Because of this, there were many injuries and deaths. To avoid this particularly lethal danger we had chosen to climb in cold conditions when the rocks were more likely to be frozen in place. Then, the safest time would be the coldest days in the mid-winter. However, due to short daylight and severe coldness, the cold days of spring became our choice.

Since 2011, every spring I prepared a trip to climb the Eiger Nordwand. During the preparation that year, I didn’t know it but I had a hairline crack on the right femur from a bicycle accident in September and the pain hadn’t gone away by the spring. So, I cancelled the trip and went to see a new doctor who managed to find the problem. He immediately operated on me to avoid a hip replacement. During that winter I had led WI 5 ice, but I could not snowplow while cross-country skiing, no wonder!

The following spring, when I was just about to leave work to go to the airport for the Eiger, my boss called and gave me a layoff notice. Darn, why couldn’t it have waited until I came back? My mind was not able to focus on the climbing, and obviously I had to cancel the trip. Luckily, the old company ended up re-hiring me for a more exciting position. By then, it was too difficult to reschedule the Eiger trip so I had to wait another year.

Unfortunately, climbing the Eiger Nordwand became more difficult for Paul. His wife worried about his safety because she had heard of the Eiger’s grim reputation. Eventually Paul had to drop out. It was foreseeable since he had two young children. I was surprised when he suggested that I find someone else to climb with. It wasn’t easy for me to climb with another partner. However, honoring his suggestion, I searched for a potential match but I could not come up with the right person. This person would have to have a strong desire to do the Eiger Nordwand. Also, he should have ample experience for potentially grievous long alpine routes and of course, a matching chemistry would be nice. After a year of searching I almost gave up.

In the spring of 2014, via an online search, I came across a prominent British climber, Jonathan Bracey, a mountain guide who lives in Chamonix, France. Although most guides would not take a client to the Eiger Nordwand, he would climb with me under certain conditions. Until this point, I had never thought of hiring a mountain guide because I had no desire to be guided. So initially, it was unappealing. By email I described my situation to him (loss of my partner). In the correspondence, I provided a list of my prominent climbs such as the Grandes Jorasses northface, solo climbing of Frendo Spur, leading extreme ice routes such as Nuit Blanche and Sea of Vapors, etc.

A plan to climb the Eiger Nordwand with Jon had rapidly formed for April of 2015. However, just before heading to the airport, he texted me not to come due to bad weather rolling in. He also suggested to wait for the weather to improve but it became too warm and unsafe to climb.

In April 2016, I finally met Jon in Chamonix. To get to know each other, we climbed a couple days of multi-pitch mixed (M5) routes near Aiguille Du Midi. Although I had already stayed at the Cosmiques hut 3 nights for the acclimatization, these climbs would add more acclimatization. It felt like being in school with my teacher observing my performance and this made me inevitably very nervous. Subsequently, I made a very rudimentary mistake - forgetting the harness’ belt loop-back through the buckle. Of course he caught me; well I was testing him to see if he would catch it, “grin.” Otherwise, the climbs went smoothly.

After climbing together, I nervously asked him if I was qualified for the Eiger. He said “Yes, you are. The Eiger climbing is our project. You are my partner, you watch me, and I watch you. So, we will have a safe climb.” The words “our project” were particularly important to me. Of course, his words “my partner” made me feel better; this was not a guided climb. I was also afraid he would deny me based on my age. However, he wasn’t surprised when I told him old I was. He and his friends (mostly French climbing guides) said they hoped to be like me when they reached 68 years old.

In addition, I was glad that I was going to climb with a British climber since it was my preferred climbing style, which is highly efficient, speedy, with improvisational techniques meaning no extra equipment. Unfortunately, the weather for the Eiger Nordwand never became favorable during the three weeks I stayed there. It would be possible to climb the Eiger in autumn, so, I decided to wait another six months. Unfortunately, I did not communicate clearly with Jon in the autumn and he was booked with other clients. Disappointingly, I would have to wait for next spring.

In April 2017, the weather was good. After the acclimatization in Chamonix, Jon and I went to check out the Eiger Nordwand. However, there were tons of fresh snow covering the north face. It would take too much time to climb it. So, we decided return to Chamonix. These were very similar conditions to my previous attempt in 2012, on which we only climbed to the Difficult Cracks and retreated as described in my article in The Crux issued on January 2013.

Unlike other years, I made a second trip to the Alps that same year in autumn. It was my 9th preparation for the Eiger. Well, this was it! I will finally make a successful climb of the Eiger Nordwand.

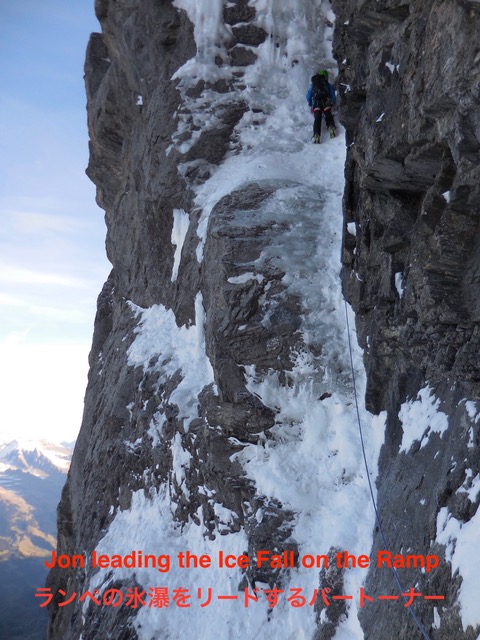

Before the climb, I had planned to spend 3 nights in the Torino hut at the 3400m (~11,200ft) for acclimatization. However on the second day, October 31st to be exact, Jon called me to come down to Chamonix since good weather moved into the Grindelwald area. Although my acclimatization was insufficient, we headed to Grindelwald. In my misjudgment, I thought I should be fine on the Eiger since I could take a rest at each pitch during belay. I was totally wrong. We climbed continuously, and took belays only for a few sections. We climbed all day without resting, from dawn to dusk.

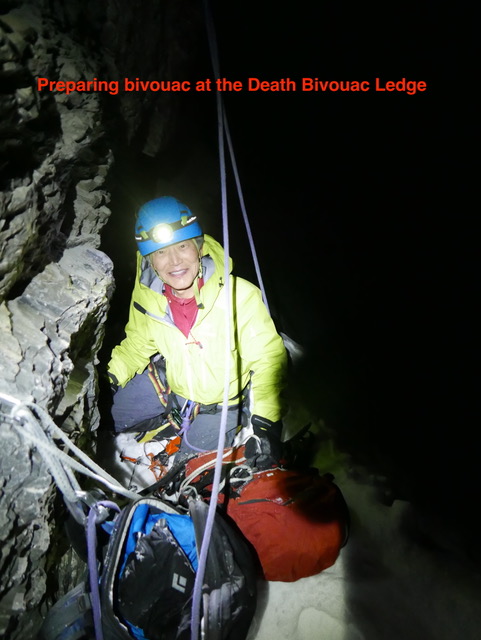

We arrived at the Death Bivouac ledge after 12 hours of climbing, and this was our planned stop for the first day. We bivouacked on Halloween night at the ledge, but no trick-or-treater visited us! Fortunately, I didn’t think of the spookiness of Halloween nor of the two climbers who died on this ledge in earlier attempts.

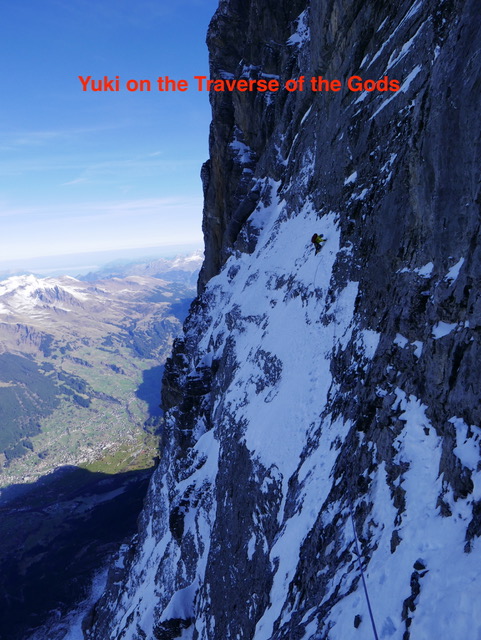

When we were simultaneously moving, depending on the terrain, we always had at least one or more running belays (gears) between us. At the Traverse of the Gods, we moved simultaneously with complete confidence, absolutely no feeling of “run- out.” It was a spectacular view, but I couldn’t enjoy it since we were moving fast and non-stop.

On the Exit Snowfields, the inadequate acclimatization began to affect me drastically. I had to make frequent brief stops for deep breaths. Eventually I reached the summit ridge; the north face was behind me. It was getting dark, and we turned on our head lamps. I figured it would take much more than an hour to the summit, and I wasn’t sure if I had enough energy to make it. So, I asked Jon if we could bivouac there. “No!” He firmly encouraged me to push to the summit because it would be too dangerous to to stay there. Indeed it was steep with frozen, hard snow, and we could not bivouac safely. I was really a zombie, but I was determined to make it to the summit, no matter how long it would take. Fortunately, the Mittellegi Ridge started very shortly, and it was not too steep. I was pleasantly surprised to arrive at the summit in about an hour. It took a total of 13 hours to the summit.

We flattened down the snow for a bivouac and removed our harnesses for the first time since the beginning of the climb. There was a clear sky with a mild breeze, but it was not so cold, perhaps around 10 deg-F (-12C). After the frozen-dehydrated dinner, I snuggled into my tight-fitted 3-season down sleeping bag with my down jacket over the bag.

I composed an email on my iPhone to my families and friends inside the GoreTex bivouac sack. My fingers got cold very quickly, so it was a short message - “I finally made a successful ascent of the north face of Eiger by climbing the 1938 route. We bivouacked the death ledge last night and are bivouacing at the summit now. This email is from the summit of Eiger. My. fingers are getting cold. I’ll write more later.” Too cold to check the spelling, of course, and sent it!

We woke up at sunrise. Jon asked me how I slept. I had slept very well, but he had not slept at all. I didn’t notice until that morning that his sleeping bag looked very thin; it could be a light summer bag. No wonder his pack was smaller than mine; he had a 28-liter pack while mine was a 38-liter.

Descending the West Face from the summit was not so simple. We had to navigate by connecting several snow fields which were separated by ice or rock bands. At the ice and rock sections we had to rappel down. The navigation would require a clear view of the west face. Fortunately, we had a clear morning. We un-roped only where the snow was in good condition to walk down safely. It took almost 5 hours to the Eigergletscher train station.

Our climb was picture perfect, executed without any epic, injury or even scratches or bruises. As anyone who goes to work at an office and expects to go home safely without any epic, this also applies to mountain guides, and Jon did so on the Eiger. I watched his safe techniques, and he didn’t take any chances. He backed up old existing gear with his or tested them.

I had accomplished my life-long objective. However, it took a few months to realize and comprehend it. When that occurred, I felt rewarded. Now, I can focus on new goals.

Postlog: The most scary moment (I thought we were really screwed):

We drove to Grindelwald from Chamonix, and took trains to Eigergletscher station. From there, we made a short walk to the upper chair lift ski station behind the train station. We found a flat snow covered area under the chair lift for pitching a tent. Without doubt it was a safe place to camp before the Eiger climbing.

At a wee hour, we heard the sound of a snow machine starting in the distance below us. I had no idea why they had to work at so late . Another hour or two later, a loud sound of the motor from the chair lift woke us up. Several minutes later, our tent was suddenly scooped up from the ground. Immediately I realized that the chairlift had hooked our tent and dragged it. I envisioned our tent being lifted in the air and dropped off onto the steep slope below. After being dragged a few feet, our tent was suddenly unhooked. Jon opened the tent door and started talking to the man who just got off from the chairlift. My heart was still pounding from fear of being evicted in the middle of the night. No, all we had to do was to relocate the tent about 20 feet, so that the tent won’t get caught by a chair lift. We slid the tent 20 feet and quickly fixed the broken tent pole and went back to sleep. The tent and other unnecessary items were left near the chair-lift during the Eiger climb and were picked up on the way back.