Life After The Rock Program: Crushing it in the High Sierra by Lisa Fernandez

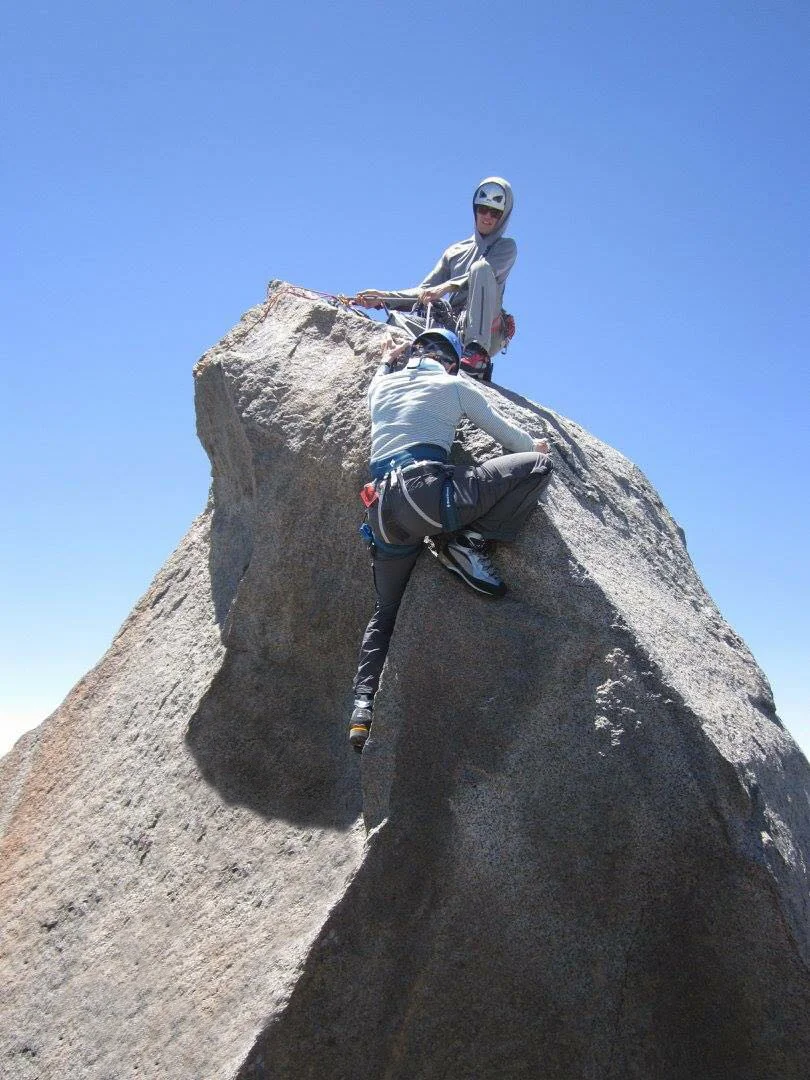

/Savoring the fifth and final summit of the Palisade Traverse: Mount Sill

Crammed in the middle, age-wise and bodily, on a tiny bench between my 84-year-old mother and my 16-year-old daughter, I was craning my neck upward, straining to make out the “dark llama.” It's one of the sky forms the native Andean people named for the shapes in the sky between stars in the milky way. We were at a small planetarium in Cuzco, the so-called navel of the Andean world, on our last night in Peru, learning about the ancient astronomical scholarship that informed so much of Incan and pre-Incan construction in this high mountain aerie. The guide was explaining some popular mythology about how the natives connected what they saw in the heavens to their life on earth: the milky way, they observed, nourishes the glaciers that form the immense peaks surrounding us. The glaciers feed the rivers, which in turn water the plants and animals and people, so the milky way brings life into being.

I could relate. In the black, cold night we tried to find the Southern Cross. It barely peaked out over the horizon where we were on Planet Earth – just south of the equator, in Peru’s late winter (August). Almost exactly a month earlier, only two weeks after the northern hemisphere’s summer solstice, I had watched the sky closely on another black, cold night. I was bivying on the shoulder of North Palisade Peak, in the middle of a guided traverse at the south end of the Sierra Nevada range of California.

That trip was the culmination of my spring and summer of training. It began with Knot's Night in late March, and continued through weekends during April's mud season where I wrestled with rope techniques at the Quincy Quarries. From there I went on to practice at the Gunks and Acadia in May with the rest of my fellow graduates of the Rock Program. I also enlisted the help of a personal trainer and got my arms in shape at my local climbing gym with many hours of wall shuttles that simulated the technical pitches I could expect out west.

I’d had a setback which almost cancelled the trip: in June just three weeks before I was scheduled to fly out to California, I’d been practicing at my only in-town climbing area, a 200-million-year old slab of basalt called West Rock. The cliff itself is beautiful, in 2 to 3 pitches rising above the trees for views of the gleaming Long Island Sound. But it’s also very dirty, with lots of loose rock, partly because it hasn’t been climbed much so loose chunks haven’t been cleaned out. The hardware on the climb my friends and I chose were shiny bright and brand new. It had only been bolted a few days before our attempt. While hanging out at the base of the climb waiting my turn, I heard the leader yell “ROCK” and ran away from the cliff. Wrong. The rock careened down the face, bounced at the base, right into my left ankle where it was cut cleanly to the bone (always run toward the cliff, not away, apparently). As the blood started to well thickly out of the wound, another fellow climber commented, “looks like muppet mouth.”

I blubbered at the doctor’s office as he stitched me up. Not from pain, but because he was telling me he couldn’t be sure the ankle would be sufficiently healed to wear boots and climb so soon. What I remember through the uncontrollable disappointment I felt, was his remark, once he learned where I planned to go. “I want to take my daughter there, where she can see the Milky Way. Around here, there’s too much light pollution” he said. I hadn’t thought about that before, that one reason to climb is to get closer to true darkness, where you can truly appreciate how lit up the night sky is.

Since reaching the ripe old age of 50 five years ago, I’ve tried to become more disciplined about ticking off some goals on my growing bucket list. Almost the entire list consists of mountaineering ventures, many of them involving peak bagging, including all fifteen of the peaks over 14,000 feet in California. I’d lived in the high country in Yosemite in my early twenties, but I’d naively felt immortal at that time, the years in front of me to tackle big peaks a seemingly endless progression of decades. So back then I only casually bagged a couple of those summits.

Now, it’s past time to get serious, and the challenge has become greater: I live at sea level on the east coast, thousands of miles away from my beloved “range of light” as John Muir coined the Sierras in his romps there nearly two centuries ago. So there I was on a wet Saturday at Quincy Quarries just outside Boston, in a mix of sleet, rain, and snow, trying to embrace a piece of vertical rock. It was brightly bedecked in enamel paint graffiti which, in the icky conditions, made the climbing that much harder. Not that it mattered in my case, because I had come clad to follow a leader in my new mountaineering boots, which I was trying to break in for the Palisades trip. My guide for the Palisades had insisted they were the right footgear for the technical climbing we would be doing: up to 5.7 or so, over multiple pitches on rock and potentially ice and snow, at 14,000 feet with lots of exposure. I felt like Sisyphus at QQ, and I know I looked ridiculous. In the stiff, steel-shanked boots I would scramble up a move only to slip and fall off. The boots, bright blue and bulky, would have looked better on the set of Star Trek. All I could think was “how can I possibly manage a 5.7 in these boots, at an altitude where I’ll barely be able to breathe, on possibly icy, possibly wet rock?” I consoled myself with the thought that at least there’d be no graffiti that high up.

At my age, returning to climbing was humbling. During the Rock Program, I routinely felt like an artifact from a previous era, which, I have to admit, I was (you caught that Star Trek reference, right?). I had learned to climb in college more than 30 years prior, when harnesses were wide pieces of nylon webbing stitched together, the most advanced belay device was a figure eight, and the first climbing gym was still more than five years into the future. I had quit climbing to focus on building a career and a family.

Now I was approaching the other end of those endeavors, and the mountains were calling me to clamber up them before advancing decrepitude kicked my butt. To bag the five 14’ers in the Palisade traverse, I had to get on a rope, and I had to brush up on class 5 climbing. So here I was at QQ, in my Trangos, yelling “on belay!” up past some garishly decorated rock that was making me feel dumb and reminding me that I wasn’t exactly nimble or lithe. Though most of my fellow trainees were on average 20 or more years younger than me, I was relieved to see that many of the instructors were closer to my age. Phew! They probably started climbing around or even before I did, but never gave it up like I had. For me, it was a total time warp: fun, scary, and yeah, even a little (or a lot) crazy. The good thing was that despite feeling old and awkward, the Rock Program did prepare me well for “my summer in the Sierras” (as Muir would say). And my ankle, though still wrapped in gauze and tender, seemed sufficiently strong enough to attempt the trip.

The time warp I’d been feeling throughout the Rock Program training continued once I got out west. My fellow clients and guides were all millennials. They were also all guys and they outnumbered me four to one. I refer to the trip now as “bromancing the stone” because though the conversation with these dudes was often hard to understand, they shared my love of the mountains. Together, we sent those peaks in high style. I did miss the strangely cozy urban ambience of QQ during the predawn climb over expansive snowfields and up the steep north couloir of the Palisade Glacier. I missed it later, too, as I hugged an arête, blindly feeling for the tiny ledge to stand on. It was somewhere around the other side, with two thousand feet of pure air straight down to talus just an inch past my brightly clad toe.

clawing our way up the north couloir of the Palisade Glacier on the way to Thunderbolt Peak

The first peak we reached was Thunderbolt. The very top is an anvil-shaped block, requiring a dyno move up over a bulge using a heel hook. I had never heard of a heel hook during the Rock Program or at any other time in my life. It was rated 5.9-plus. That was two grades above anything I had ever tried. No matter. The Trangos performed and so did I, with my heart in my mouth and my guide holding a nice tight line on me.

After two more summits and the constant sensation of being one footfall from falling into the air, we rappelled down at sunset to a narrow ledge where we spent hours melting snow for drinking water and slurped Mountain House right out of the bag. Because it was a new moon, the night was very dark, and the sky shone with a blanket of stars so numerous and bright that the constellations we all know could not be discerned. I couldn’t sleep, and all night I watched the Milky Way slowly turn. It was embodied and muscular, a sculpture in the sky. It fed me and the mountains so deeply and completely that the next day, we rocked it up the remaining Palisade peaks as if made of the same stuff as those stars.

Descending the south icefield, with some of the peaks that form the Palisade Traverse in the background

On my list, I’ve still got 5 California 14'ers to go. I also want to do Snake Dike up Half Dome, a couple of classic climbs in Tuolumne and all those Gunks climbs I left undone back in college. I have a nice badass scar on my left ankle, and it still feels tight when I run. But the mind-bending sight of the Milky Way draws me back to the mountains every time. It’s not a lot to do in middle age if you wear the right footgear and train with the Rock Program!

Taking a break on the ascent to our basecamp (Sam Mack Meadow). A wrapped ankle and strong antibiotics got me up!